Solving Galactic Dynamo Equations and Exploring Fountain Flows

Abstract

Study of the non-linear dynamo equation in the context of scales relevant to galaxies is pivotal to get an insight into the dynamos that generate the magnetic fields of galaxies. In this project, we have investigated the dynamo equation, starting off from the Induction equation. We have observed how diffusion comes into play, and adding alpha-omega terms at certain levels makes the dynamo action active. We also add the fountain flow term in the dynamo equation and see how the fields change over time.

Introduction

All phenomenons of large-scale magnetic field generation are modelled using equation of Magnetohydrodynamics. To start off, we essentially write the Induction Equation in terms of the Mean Field Component of the Magnetic Fields. On writing this equation in cylindrical coordinates, we get three equations dictating the evolution of Magentic field components in the $r$, $\phi$, and $z$ components of the equation. First to see how the dynamo is actually powered up through the $\alpha$, $\Omega$ dynamo, we shall do a part by part analysis. We also wish to explore fountain flows in Galaxies and how they affect dynamo equations. We have taken theoretical motivation from (Rodrigues et. al., 2019). Thus we first have the induction equation which is given by

Then we do a component seperation of these fields. We decompose all the physical parameters into two components, one being the large scale mean field components and the other part is the random or turbulent component. Thus for every vector field of interest, say $\mathbf{A}$, we decompose it as follows:

Where the barred component is the mean field, and the component in lower case is the turbulent component. Thus, if we do a average over scales larger than the scales of the turbulent component, we are only left with the mean field component, and we will deal will the equations obtained by this method. It is valid to question as to why are we neglecting random fields for this part. Given the physical scales of a galaxy, it is safe to do this averaging. We must also note that the effect of turbulence is not actually entirely removed. Turbulence components tend to diffuse out the energy from the large scale magnetic fields, and the turbulence component is actually accounted for by the diffusivity parameter $\eta_t$.

Where $\tau$ is the timescales for turbulent flows, and $v_{rms}$ is the typical turbulent flow velocity. We therefore have accounted for turbulence in a simpler fashion by this parameter $\eta_t$. Now for the dynamo to amplify the magnetic flux, we need to $\alpha$-$\Omega$ effect. This competes with the diffusion term to generate higher mean field amplitudes. We need atleast $\alpha$ and $\Omega$ effect for this. For our case of analysis, we have neglected $\alpha^2$ effect. I will shortly desribe these effects more rigorously in coming sections.

Thus we have a picture now that, turbulent motions tend to diffuse out the magnetic field strength. If there is some machineary which transports the turbulence out of system, then it should help in retaining the large scale fields. Fountain flow is one such machinery. Essentially, gas when heated up by supernovae expands and rises above the plane of the galaxy, transporting the small scale turbulences along with it.

Some studies (Vainshtein, Samuel, 1992) suggest that the Lorent force due to rapidly growing small scale magnetic fields, can render the large-scale dynamo ineffective, producing only a negligible mean field, which in contradiction to what we actually have.

Thus we study the effect of fountain flows in the $\alpha$-$\Omega$ dynamo, and see how it changes the usual scenario.

Numerical Methods

Runge-Kutta Method

The Runge-Kutta method is a numerical technique used for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs). It is particularly useful when analytical solutions are difficult or impossible to obtain. The method involves approximating the solution at discrete points within the interval of interest. Among the various forms of Runge-Kutta methods, the most commonly used is the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method (RK4).

The general formula for RK4 is as follows:

\[\begin{align*} k_1 &= h \cdot f(t_n, y_n) \\ k_2 &= h \cdot f(t_n + \frac{h}{2}, y_n + \frac{k_1}{2}) \\ k_3 &= h \cdot f(t_n + \frac{h}{2}, y_n + \frac{k_2}{2}) \\ k_4 &= h \cdot f(t_n + h, y_n + k_3) \\ y_{n+1} &= y_n + \frac{1}{6}(k_1 + 2k_2 + 2k_3 + k_4) \end{align*}\]Where:

- ( \(t_n\) ) represents the current time step.

- (\(y_n\) ) is the solution at time ( t_n ).

- ( h ) is the step size.

- ( f(t, y) ) is the differential equation being solved.

- (\(k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4\)) are intermediate slopes calculated based on the function ( f(t, y) ) at various points.

This method iteratively calculates the value of the function at each step by using weighted averages of different slopes. The RK4 method is known for its accuracy and stability, making it a popular choice in numerical analysis for solving differential equations.

For the radial derivatives of magnetic fields we have used numpy.gradient function, which essentially implements the finite difference method for derivatives.

Finite Difference Method

The Finite Difference Method (FDM) is a numerical technique used for solving differential equations, including partial differential equations (PDEs). It works by discretizing the differential equation into a system of algebraic equations by approximating the derivatives with finite differences. FDM is widely used in various fields such as engineering, physics, and finance.

For example, consider a one-dimensional heat conduction equation:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} = \alpha \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x^2}\]To solve this equation using FDM, we discretize the spatial and temporal domains. Let (u_i^n) represent the value of (u) at spatial point (x_i) and time (t_n). Using central difference approximation for both spatial and temporal derivatives, we can rewrite the equation as:

\[\frac{u_i^{n+1} - u_i^n}{\Delta t} = \alpha \frac{u_{i+1}^n - 2u_i^n + u_{i-1}^n}{(\Delta x)^2}\]Where:

- ( \(\Delta x\) ) is the spatial step size.

- (\(\Delta t\)) is the temporal step size.

- (\(\alpha\)) is the thermal diffusivity coefficient.

This equation can be rearranged to solve for \((u_i^{n+1})\) in terms of known values at time step n. The process is repeated for each spatial point and time step until the solution converges.

FDM allows for the solution of differential equations on a discrete grid, making it computationally feasible for complex problems. It is versatile and can be applied to various types of differential equations with appropriate discretization schemes.

Courant Condition

The Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) condition, often referred to simply as the Courant condition, is a stability criterion for numerical methods used to solve partial differential equations, particularly those involving wave propagation. It ensures that the time step used in the numerical scheme is small enough to accurately capture the dynamics of the system.

The Courant condition is derived from the physical principle that information cannot propagate faster than a certain speed within the system. In the context of numerical methods, it states that the time step \(\Delta t\) used in the simulation should be chosen such that the distance traveled by any information in one time step is less than or equal to the spatial resolution \(\Delta x\) of the discretized grid, multiplied by a factor called the Courant number \(C\).

Mathematically, the Courant condition can be expressed as:

\[C = \frac{v \cdot \Delta t}{\Delta x} \leq C_{\text{max}}\]Where:

- \(v\) is the speed at which information propagates within the system.

- \(\Delta t\) is the time step.

- \(\Delta x\) is the spatial resolution.

- \(C_{\text{max}}\) is the maximum allowable Courant number, typically determined empirically based on the stability requirements of the numerical method.

If the Courant number exceeds \(C_{\text{max}}\), the numerical solution may become unstable, leading to unrealistic or erratic behavior. Therefore, it’s crucial to adjust the time step according to the Courant condition to ensure numerical stability and accuracy in simulations involving wave-like phenomena.

For our case we have a slightly different definition of Courant condition, where

\[C = 2\eta \frac{dt}{dr^2}\]as this ensures that the range of diffusion is limited to our cells which define our resolution.

Methods

For ease of analysis, we have assumed a no-z approximation, that is for a thin disc, the derivatives along $z$ can be essentially replaced by corresponding ratios. Thus the equations for this case is essentially

The derivatives with respect to z are then estimated as

For the first part, we neglect all field sustaining effect, and just look into the diffusion equation. We neglect all couplings between $B_r$ and $B_{\phi}$. We also neglect the $\alpha$ and $\Omega$ terms. Thus we consider only the terms involving $\nabla^2$. Hence, at this stage, we essentially have only the diffusion terms, and our equations are as follows.

We see that the magnetic fields dissipate quuickly in this case, and dynamo is not in action as shown in the results section. Now we proceed to add the $\alpha$ and $\Omega$ terms, neglecting the $\alpha^2$ effect. That is we neglect the term involving $\alpha$ in the evolution equation for $B_{phi}$, and retain the terms having $\Omega$, and $\alpha$ for the evolution of $B_{r}$. Then we have,

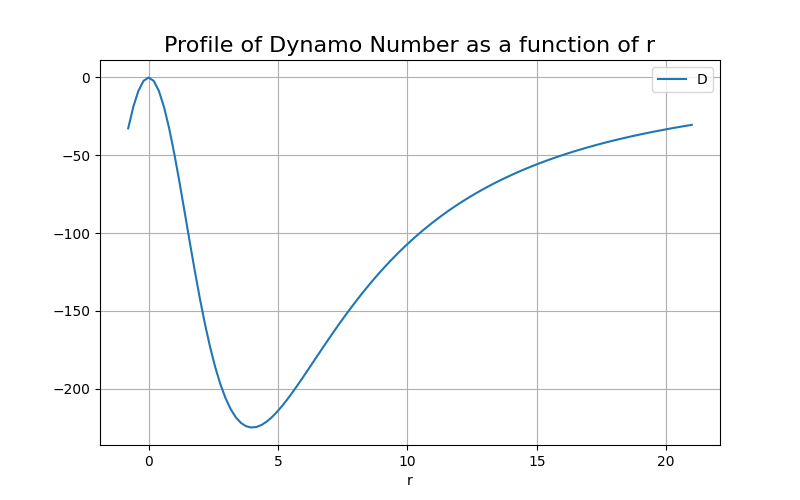

The inclusion of this terms essentially accounts for the $\alpha-\Omega$ effect. To get a better physical picture, $\alpha$ term essentially turns the toroidal field into poloidal field in cylindrical geometry, and $\Omega$ term turns poloidal field into toroidal field. These factors compete with the diffusive terms, hence for a specific case of $\alpha$ and $\Omega$, with respect to $\eta_t$. Thus we define a quantity called the dynamo number, which is defined as:

Where $h$ is the scale height at each point of the galaxy, along z. This essentially quantifies, whether we will have a growing solution, or decaying solution, or a saturating solution. For a typical dynamo number (we average over all r), called critical dynamo number, we essentially have the saturating solution. In this case, only for a dynamo number that is greater than the critical dynamo number, we have a growing solution.

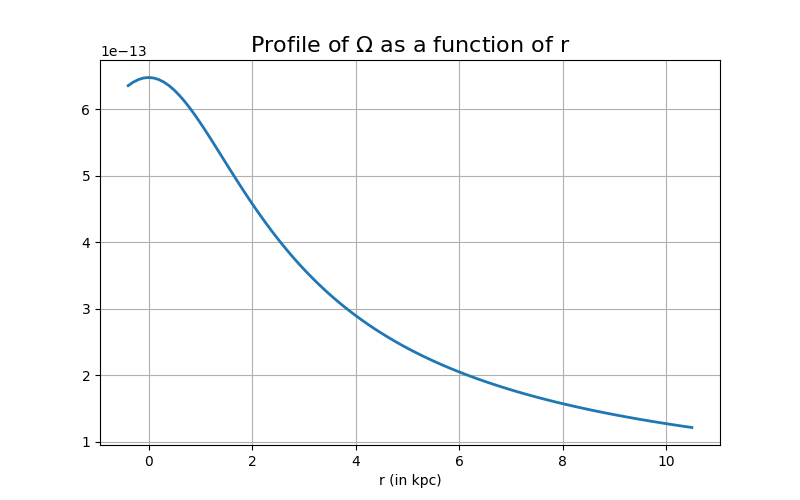

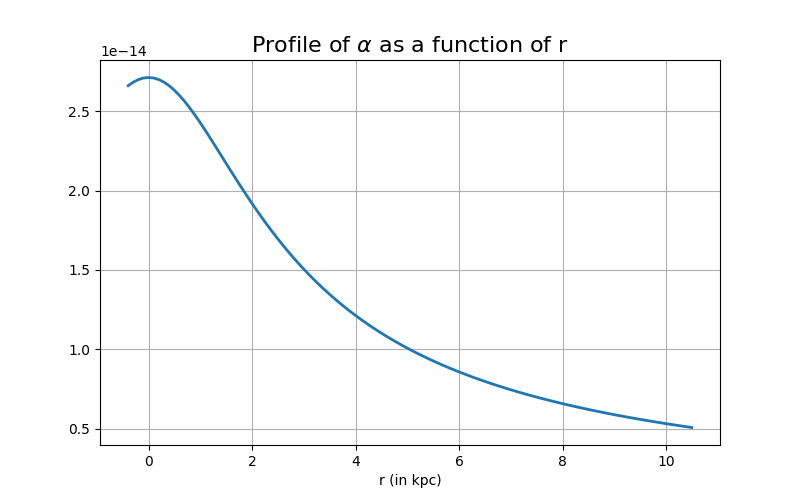

For the choice of $\Omega$ and $\alpha$, we take a functional form described as:

We fix \(R_0\) to a specific value, and proceed with the analysis. For $\alpha$ we have then,

Depending on the interplay between these, we get the necessary solutions.

Now, we include the terms of fountain flows. We assume that the radial outflow is negligible, thus the radial velocity term is neglected (\(\bar{V_r}\)), retaining only flow perpendicular to the disk i.e., \(\bar{V_z}\).

We expect outflows outward within the luminous disk of the galaxy, for our consideration, we assume a constant outflow at all radius to start with. Another feasible part is when we have decreasing $V_z$ over r, which essentially means, the fountain flows decreases as we go towards the end of the galaxies.

Results

Solving for the case of diffusion equation, we end up with a solution, in which whatever existing field is there, they diffuse out, and the field strength reduces drastically. The example cases are given below.

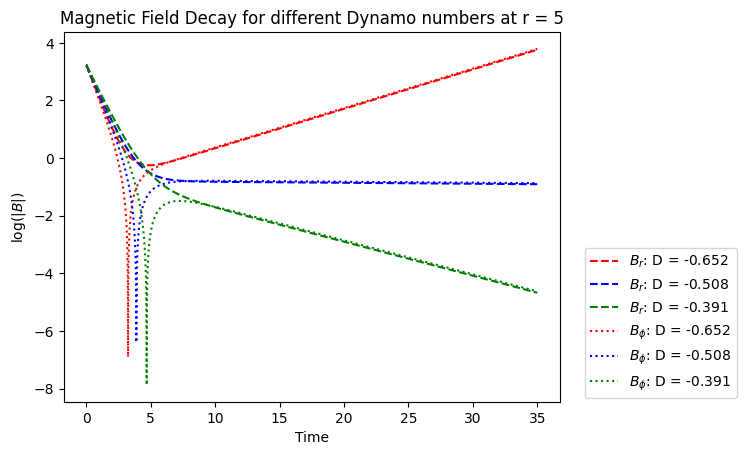

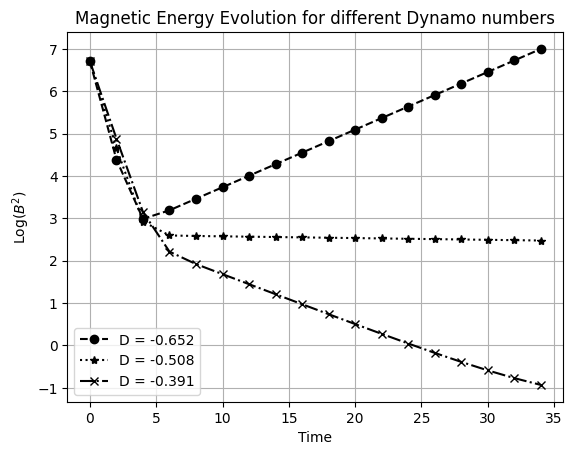

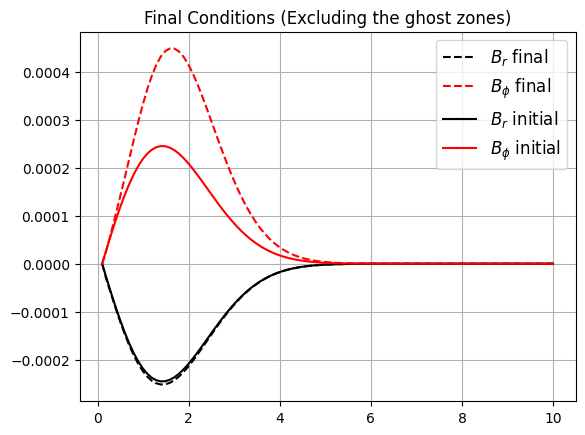

This is what we expect, in the case of diffusion. Now coming to the case of $\alpha-\Omega$ dynamo, we have three different cases, that we have analysed in arbitrary units.

We have also compared the the evolution of the magnetic field, at a specific location, for our case it was r=5 (code units, the choice is arbitrary). We have seen that, in the initial time steps, the diffusion dominates, but at a specific point the $\alpha-\Omega$ effect starts pumping up the magnetic field. When observed at a global scale, the net magnetic energy increases as well (which is proportional to $B^2$). For the critical value of D, we have observed that the growth becomes zero, after some time, and at the other extrema, a decay in the magnetic field energy is observed.

The codes for this part can be found here.

The corresponding $\alpha-\Omega$ for this specific case can also be illustrated as follows

To compare our results with the standard results provided, we have the following result as well.

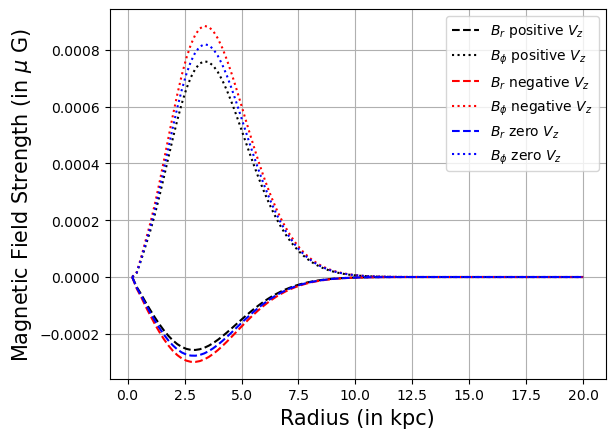

Now that we are done with this part, we proceed with further analysis, as to how $V_z$ variation will affect the dynamo. The typical range of vertical galactic outflows, averaged over the scales of the galaxy can be approximated to be at most 2 km/s (Shukurov et. al., 2006). Thus, we only consider the case, where over the radial scales of interest we have either a positive constant, or negative constant vertical velocity, of the corresponding value.

When the $V_z$ is zero, we retrive the usual dynamo evolution. When we have a positive $V_z$, as evident from the equation, it will try to decrease the magnitude of the magnetic field, over time. Which is just the opposite when it comes to the negative case. Thus it either slows down, or enhances the usual dynamo, based on how strong it is with respect to the dynamo

This can also be verified analytically by solving for only thr fountain flow term on the RHS of the equation, and see how it just adds an exponential growth or decay. If we compare the global growth rates for each of the cases, this will be more evident.

Conclusions

Our analysis is elementary, and has many simplifying assumptions. Our approximation is not valid for elliptical galaxies, limiting ourselves only to spiral galaxies. We have not gone into the non-linear regime, and thus what we observe in this analysis are merely based on this very simple equations. There are other turbulent factors that may be relevant. For our case of analysis, we have used a constant $V_z$, which can be extended to a variable outflow in the vertical direction, by extending further away from the typical galaxy radius, we need more detailed analysis to get a more realistic results. We have strictly kept ourselves in the mean field equations only, without any turbulent field equations coming into play, which is not a realistic scenario, but the only way we have encoded turbulence is through thee definition of $\eta$, which is a simpler way of modelling turbulence. This analysis can thus be extended to much more realistic situations, if we choose necessary forms of the different parameters. As a basis, this analysis is elementary, but has scope for further extension.

Please find the codes here: Github

References

- Vainshtein, S. I. & Cattaneo, F. Nonlinear Restrictions on Dynamo Action. The Astrophysical Journal 393, 165 (1992).

- Shukurov, A., Sokoloff, D., Subramanian, K. & Brandenburg, A. Galactic dynamo and helicity losses through fountain flow. A&A 448, L33–L36 (2006).

- Rodrigues, L. F. S., Chamandy, L., Shukurov, A., Baugh, C. M. & Taylor, A. R. Evolution of galactic magnetic fields. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 483, 2424–2440 (2019).