Correlating Synchrotron with Galactic Magnetic Field

Motivation and Theoretical Background

In this project we use Minkowski Functionals to test the non-Gaussian nature of the Galactic synchrotron foreground emission. We use full-sky map of 408 MHz Haslam map as a tracer of Galactic synchrotron emission. Rahman et al., 2021 paper found that the 408 MHz map can be approximated as a Gaussian distribution over the high Galactic sky at the angular scales smaller than 3 degrees. Using simulations of the synchrotron emission with a large-scale Galactic Magnetic Field (GMF) including random turbulent component, we aim to relate the observed statistical properties of the 408 MHz sky with the properties of the Galactic magnetic field.

In order to study the properties, we first do a theoretical modelling of the Synchrotron Emission, along with a modelling of possible geometries of the Galactic Magnetic Field. Using the corresponding models, we have used parameters to define the geometry from best-fit models obtained through simulations using a Markov-Chain Monte-Carlo parameter space survey (Pelgrims et al., 2021).

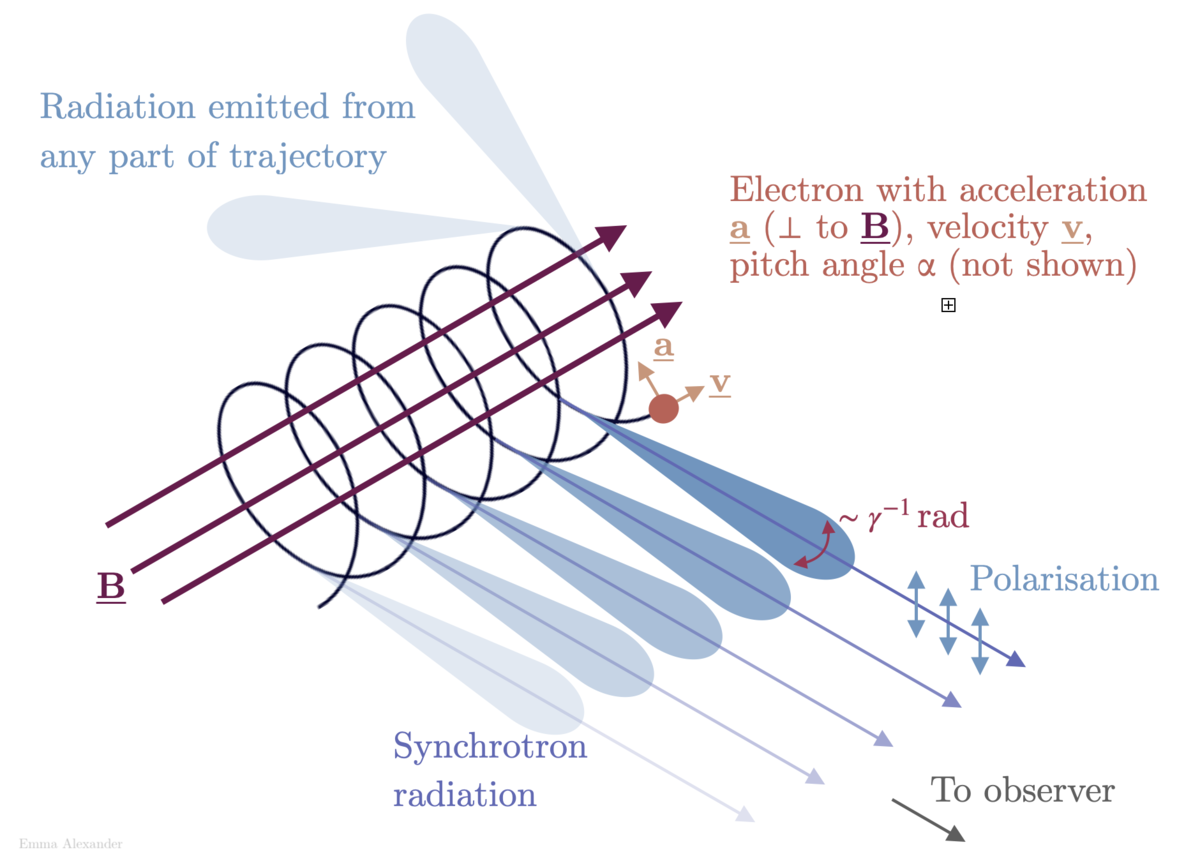

Synchrotron Emission

The Galactic Synchrotron emission is produced when relativistic electrons swirl around the GMF Lines (Rybicki and Lightman, Radiative Processes in Astrophysics). This emission is supposedly polarised perpendicular to the GMF lines. As shown in figure, the relativistic electrons swivells around the magnetic field line (B-Field), with their axis of revolution parallel to the direction of the magnetic field. This shows that the synchrotron emission is polarised in a direction perpendicular to the magnetic field as shown in the figure.

We are specifically interested in contribution of synchrotron to the Cosmic Microwave Background at high frequencies.We assume a power law distribution for the energy of relativistic electrons, i.e., we assume that the number of electrons in a specific energy range can be approximated as follows:

The variable $E$, can as well be replaced by the Lorentz factor $\gamma$, and in such case, we can also write the power law dependence as follows:

Where the variables have been written as a function of the Lorentz factor, and the above equation is assumed to hold for a given energy range.

Taking only the components of Magnetic Field perpendicular to our Line of Sight vector, we proceed to evaluate the Stokes parameters as follows:

Where $I_s, Q_s, U_s$ are the the Stoke’s parameters for synchrotron emission.

- $\epsilon_\nu^s$ is the synchrotron emissivity

- $n_e(r,\hat{n}$ is the local dust density of relativistic electrons, at a direction $\hat{n}$ and at a distance r from the origin.

- $\Pi_s$ is the intrinsic degree of polarization, which is related to the spectral index (s) as follows:

- The angle $\alpha$ is the local polarization angle and is given by:

Where, $B_\theta$ and $B_\phi$ are the local transverse components of the magnetic field in the local spherical coordinate basis ($\hat{r},\hat{\theta},\hat{\phi}$).

Also, we note that $B_\perp = B(r,\hat{n})sin \chi$, where $\chi$ is the inclination angle of the GMF lines with the line of sight vector, with $B(r,\hat{n})$ is the total magnitude of the local magnetic field. In this project, we are only interested in the total intensity sky map for the corresponding Synchrotron emission, which is described by the equation for total Intensity. The Intensity maps are generated by using the parameters obtained through most likelihood fitting of parametric modles with the Planck map, as done in Pelgrims et al., 2021. We have just used the best-fit parameters to generate the total Intensity maps.

Angular Power Spectrum

When it comes to an one dimensional function, in a given interval, we can expand the function in terms of the Fourier components, and basically the Fourier components and phases, entirely describe the function in that given interval. For an all sky temperature map, which is described by the function $T(\theta, \phi)$, we can write:

Where $Y_{\ell m}$ are the spherical harmonics, and:

$P_l^m$ being the associated Legendre polynomials. Larger values of $\ell$ correspond to smaller scale structures in the map. For a Gaussian and isotropic field on the sphere, we have:

Since for each multipole $\ell$, there are $2l+1$ values of $m$, we arrive through some mathematical adjustments to:

We see that at smaller values of $\ell$ we have smaller numbers of $m$ to average over, making the average significantly different from the true average. This is called the Cosmic Variance. At larger $\ell$ values, this no longer happens to be a limitation. For each $\ell$ value, the angular scale is of the order of $2\pi/(\ell +1)$ radians. The power spectrum is basically a two point correlation function. Suppose we want to investigate the field values, then the angular correlation function is given by:

Where, $\chi$ is the angle between the directional unit vectors $\hat{n_1}$ and $\hat{n_2}$.

When it comes to a masked map, we also expand the window or mask function $W$ in terms of the spherical harmonics, and find the power spectrum of the map, removing the portions covered by the map. Although this power spectrum is the pseudo power spectrum, and is different from the true power spectrum, we can relate the ensemble averages of the power spectrum through the mode-mode coupling matrix (Hivon et. al, 2002).

Statistics through Minkowski Functionals

In order to obtain statistics of the Total Intensity maps from the simulated parameters, we essentially treat the sky map as a Random field on a sphere ($\mathbb{S}^2$). Since we have only one realisation available at hand for each pixels, or points on the sphere, we take the assumption of ergodicity, to get statistics from this one realisation of the Random field, which here is the Total Intensity ($I_s$) values at every points of $\mathbb{S}^2$. The assumption of ergodicity is based on the fact, that by averaging over volume, we can compensate for the lack of more realisations. Although, this is true for Gaussian fields, it has not yet been proven to be true for non-Gaussian fields. Neverthless, we ignore the warning like a physicist, and proceed to study the statistical non-Gaussianity of the Random field under consideration here.

We will now explain, how we can come up with a Probability Distribution Function (PDF) for the Random field on a sphere ($\mathbb{S}^2$). We assume, that the space is homogeneous, i.e., the PDF remains unchanged if we move around the space under consideration.

We take the random variable ($\delta T$) to be defined on each point of the sphere(Buchert et. al, 2017). The variable is then described by a probability distribution function $P(t)$. Where $t \in \mathbb{R}$ ($\mathbb{R} $is the set of all real numbers), and $P(t) \ge 0$. We can obtain the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) from $P(t)$ as follows:

We note that, $F(\tau)$ is a non-decreasing function and $prob(\tau_2 - \tau_1)$ = $F(\tau_2)-F(\tau_1)$. For a continuous function $ f $: $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$, $f(\delta T)$ is again a random field, whose expectation value is defined as:

To describe a PDF, we calculate and chack the moments, central moments and the corresponding cumulants. These can be done in the usual way by moment generating functions and algebraic manipulations for different probability distribution functions.

- Moments($\alpha_n$) = $ \left<(\delta T)^n\right> $ = $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} t^n P(t) dt$, $n=0,1,2,\dots$

- Central Moments($\alpha_n$) = $ \left<(\delta T - \mu)^n\right> $ = $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}(t-\mu)^n P(t) dt$, $n=0,1,2,\dots$

The corresponding moment generating function is defined as:

Now from the moment generating function given in the above equation, we obtain the Cumulant Generating Function:

The first few moments and cumulants are $\alpha_0 = m_0 = 1$, and the mean values are $\mu = \alpha_1 = \varkappa_1$. We obtain the following recursion relations then:

and similarly, for $n\ge 2$

We see that any odd non-vanishing central moment $m_{2n+1}$ of the PDF corresponding to the random variable $\delta T$, is basically a measure of the skewness of $P(t)$. We can therefore take a generic Gaussian PDF, find the cumulants and moments, and compare the same with our obtained PDF. The difference shall necessarily indicate deviation from the Gaussian behaviour of our PDF that dictates the distribution of values for the random variable of our interest.

We also see that for a given realisation of the random field, and with the assumption of ergodicity, we can establish a connection between the Minkowski functionals and the corresponding PDFs (Buchert et. al, 2017). For example, we pick up the example of the first scalar Minkowski Functional $V_0$. We consider the compact excursion set \(\mathcal{Q}_{\nu} \in \mathbb{S}^2\) with corresponding boundary \(\partial \mathcal{Q}_{\nu}(\nu = t/\sigma_0)\):

We define the MF $V_0(\nu)$ as:

We define a normalized MF $v_0(\nu)$ that is normalized with respect to area ($\mathbb{S}^2$) = $4\pi$:

Then, we can also write:

We can also write the above equation in terms of the derivatives,

Thus, we can see a relation between the normalised first scalar MF, and we can derive relations with higher MFs and expressions involving higher moments. Then for different dimensional manifolds, we have different geometric attributes associated with each of these functions (Schmalzing et. al, 1997), as described in the table below.

| d | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| $V_0$ | length | area | volume |

| $V_1$ | Euler characteristic | circumference | surface area |

| $V_2$ | - | Euler characteristic | total mean curvature |

| $V_3$ | - | - | Euler characteristic |

Modelling of Galactic Magnetic Field

There are various models to mathematically describe the gross magnetic field in a generic galaxy. These have been described in the appendix section of Pelgrims et al., 2021. We have picked up different models, and the corresponding fitted parameters, and simulated the synchrotron maps, by using the equations for Stoke’s parameters. Finally, we have applied a mask, derived from the Haslam Map at 408 MHz, and tried to get the statistics for different scenarios.